Food Must Follow the Flag

Victory gardens and the cost of fear-based immigration enforcement

After 732 days of January, it’s February and peak garden planning time. We’re planning ours with a bit more intention than usual. Not (quite) in a bunker-building, end-times way, but with our eyes open a little wider.

Grocery prices keep climbing. The news cycles through global instability with an administration eager to posture abroad while simultaneously waging a war at home and targeting populations of people who are absolutely vital to our food system and community vibrancy. The supply chain feels fragile because it is fragile. Pretending otherwise feels increasingly dishonest. So the garden plans will linger a little longer this year.

It’s like I’m planning a victory garden, I think.

And then I stop.

Because victory gardens, despite their warm and patriotic reputation, were never only about resilience or self-sufficiency. They were a response to a crisis, yes, but also a distraction from it. A way to redirect fear and responsibility away from policy and onto households. A way to smooth over violence with slogans.

The story we’ve been told goes like this: America went to war. Farmers went to fight. Troops needed calories. Food became scarce. Ordinary people stepped up, planted gardens, and fed the nation.

It’s tidy.

It’s patriotic.

It’s also bullshit in the way half-truths usually are.

After Japan attacked Pearl Harbor in 1941 and the United States entered World War II, fear hardened quickly into policy. Longstanding anti-Asian racism intensified under war propaganda and political pressure. In 1942, President Roosevelt signed an Executive Order, authorizing the forced removal of more than 120,000 Japanese immigrants and Americans of Japanese descent from their homes and into incarceration camps.

Two-thirds of the people imprisoned were U.S. citizens, held without charges, without trials, and without any evidence of espionage. Incarceration based solely on ethnicity.

Many of the people removed were farmers. Highly skilled ones. Japanese American growers had turned marginal land into some of the most productive farmland in the country, particularly in California. They produced fruits and vegetables at a scale and efficiency that often exceeded white-owned operations.

When they were forced out, their farms did not sit empty. Instead, white-owned agribusinesses and neighboring growers moved quickly to absorb that land. Lobbying interests labeled Japanese American farmers “economic competitors,” and wartime fear did the rest. Thousands of farms were lost. Generations of agricultural knowledge disappeared almost overnight.

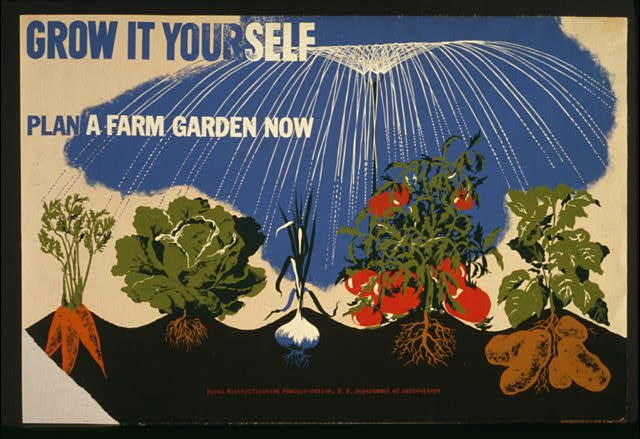

Outside the camps, the federal government launched an aggressive victory garden campaign. Americans were urged to grow food at home as munitions.

Food, Americans were told, must follow the flag.

A government guide explained that victory gardens would increase food production, lower household costs, and help families cope. It also promised something else: gardens would “maintain and improve the morale and spiritual well-being of the individual, family, and Nation.”

Gardening was not just about food. It was about morale, discipline, and managing anxiety and dissent at the household level. A way to turn structural failure into personal responsibility.

This is the version of America some people are reaching for when they talk about being “great again.” Not because it was unified, but because it looked unified. Because the violence required to maintain that image could be redistributed back onto the individual, where rising costs and empty shelves become personal problems instead of political ones.

What most people did not understand then, and what many still do not understand now, is that the food shortages and rationing of the era were shaped not only by war, but by policy choices that removed some of the most productive farmers in the country from the food system.

That part matters, because we are doing it again.

Today, we are destabilizing our food system not only through detention, but by creating fear. Creating a climate where showing up feels dangerous, regardless of documentation status. Immigration enforcement does not need to knock on every door. Fear does most of the work, pulling people out of all of the systems that keep communities functioning.

Workers with documentation stay home anyway.

Parents pull their kids from school.

People skip hospital shifts, avoid clinics, change routes, disappear.

The result is quieter than mass incarceration camps, but it operates on the same logic. Fields go unharvested. Processing plants run short-staffed. Small businesses feel it first when prices rise. Availability shrinks and food options narrow. The public is told this is just inflation, or the fault of some other country, or a personal failure.

Once again, we are creating the instability we claim to be responding to.

And once again, the solution being offered is deeply individual. Grow your own food. Be self-reliant. Pick up the slack. It turns structural failure into personal failure.

Growing food can build skills and connection. It can even offer a measure of stability. I grow food myself. I will keep doing it. But a modern victory garden cannot substitute for justice, and it cannot distract us from policy.

A garden does not replace the skilled people who grow, harvest, process, and transport our food for a living. It does not excuse raids, detentions, or the daily fear of being targeted at work. And it does not fix a system that depends on skilled, essential labor while refusing to protect, value, or respect the people doing it.

If victory gardens are going to mean anything now, they have to mean something different. They have to center labor rights, mutual aid, and resilience paired with public accountability. Gardens build connection, skills, and empathy, but they could also build political pressure.

We keep responding to food system harm by managing households instead of fixing the policies that cause it. History has already shown us what happens when a nation removes the people who feed it and calls the consequences unavoidable.

This time, we don’t get to say we didn’t know.

You know how to finesse a vitality important truth into visible reality. It’s a gift never more necessary than right now. Anyone who believes that white Christian Nationalists are going to pick fruits and vegetables, empty bedpans and bathe their neighbors in nursing homes isn’t rational.

This ethnic cleansing being sold as making everything great, needs to work a few shifts in room maintenance at their local hospital. Providing it’s still open.

Excellent piece. It’s important to expose the truth and you have done it with empathy and compassion. Thank you.